Foreign Investments and the Middle Corridor: Assessing the Caspian Region’s Landscape

Recent Articles

Author: Zhanel Sabirova

09/04/2025

Discussions about the Middle Corridor in the context of Central Asian affairs have been steadily growing, particularly as foreign investments are driving this new trade route’s meteoric growth. Although the term “Middle Corridor” has existed for nearly two decades, and earlier attempts at its realization fell short, interest was reignited after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Over the past three years, the route has been the subject of intense growth, interest, and debate. Today, the governments of the Caspian states are approaching the corridor with renewed clarity, recognizing both the heightened demand for alternative transit routes and the corridor’s potential for success.

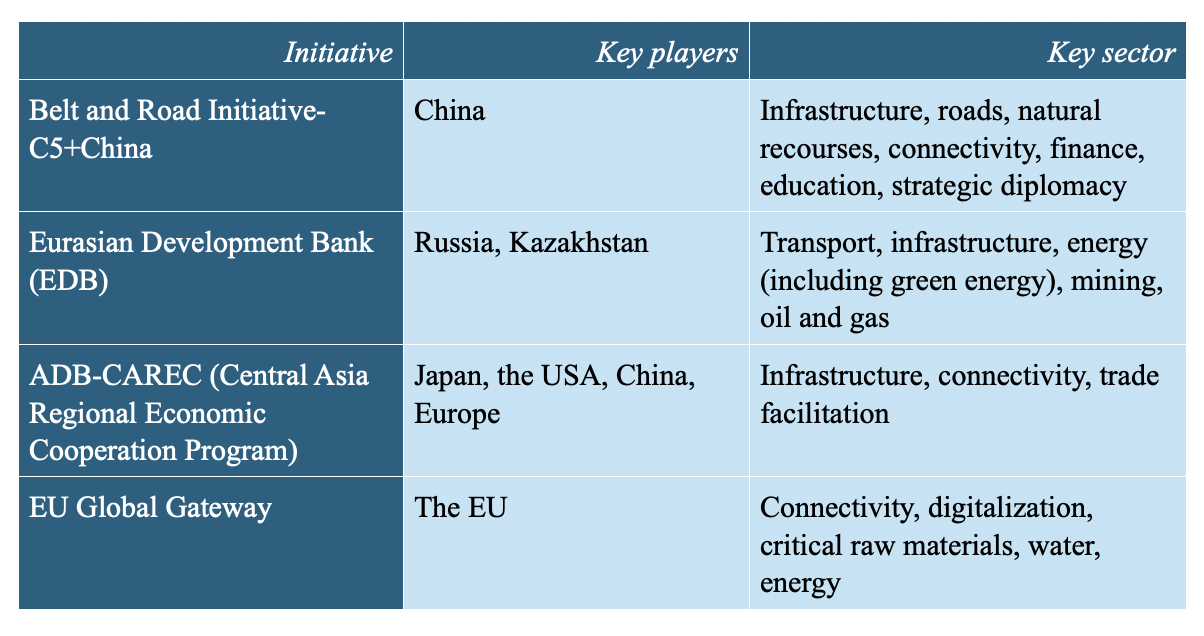

At the same time, challenges that limit capacity are becoming increasingly visible, acknowledged not only in policy discussions but also in practice. Central Asia and the South Caucasus are now deepening cooperation among themselves and with external partners to rectify these shortcomings. China and the European Union stand out as the two most influential bilateral actors in the Caspian region, pushing this evolving economic relationship, but are not alone.

Investment landscape

The investment landscape of the Middle Corridor countries is diverse, involving multiple stakeholders committed to the rapid development of the route. International financial institutions (IFIs) such as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the Eurasian Development Bank (EDB), and the World Bank (WB) have invested in infrastructure upgrades, border management systems, digital customs platforms, and port expansions. Summing up their total investments, as of 2025, the EDB’s cumulative portfolio comprised 305 projects with a total investment of $16.5 billion; in 2024 the EBRD’s cumulative investment showcased over €17 billion; to date, ADB has committed 1,054 public-sector loans, grants, and technical assistance projects totaling $36.3 billion to both the South Caucasus and the Central Asian regions.

At the bilateral level, China stands as a truly significant investor in Central Asia and the Caucasus. Over the past three decades, China’s cumulative investment in Central Asia totaled $64 billion, with direct investment exceeding $15 billion. Initially, these investments primarily focused on large-scale infrastructure projects like oil and natural gas pipelines and transportation networks to facilitate the flow of energy resources and raw materials to China through its Belt and Road Initiative projects.

At the bilateral level, China stands as a truly significant investor in Central Asia and the Caucasus. Over the past three decades, China’s cumulative investment in Central Asia totaled $64 billion, with direct investment exceeding $15 billion. Initially, these investments primarily focused on large-scale infrastructure projects like oil and natural gas pipelines and transportation networks to facilitate the flow of energy resources and raw materials to China through its Belt and Road Initiative projects.

In recent years, however, China’s investment strategy has diversified. New initiatives in poverty reduction, educational exchange, and desertification control reflect the PRC’s pivot from infrastructure-driven approach to a model more grounded in soft power, technology, and grassroots collaboration. China is no longer focused only on building roads and railways but also on involving itself in the social, environmental, and institutional life of the region.

The other key investor, the European Union, might not surpass China in total investment volume, but it offers access to different development options. Its Global Gateway initiative assigned €12 billion in investments for Central Asia, targeting transport, critical raw materials, energy, water management, and climate projects. The EU’s vision complements the EBRD’s feasibility study that identified two priority measures to address the corridor’s bottlenecks: enhancing transport links and strengthening soft infrastructure. According to the study, Central Asia requires about €18.5 billion in investment to upgrade its core infrastructure networks.

Soft infrastructure, in particular, plays a crucial role. The EU has actively engaged in bridging digital connectivity gaps across the region. As a result, in Kazakhstan, 328 villages and 2,000 schools have been connected to the internet via European satellite projects, with expansion planned to cover an additional 1,700 villages. Another success story is Georgia’s customs digitalization reform, where its overall trade facilitation score improved from 79.6 in 2019 to 90.3 in 2025, reflecting notable progress in paperless and cross-border digital trade. These reforms, supported by the EU and related United Nations programs, have reduced bureaucracy, enhanced transparency, and improved predictability in customs procedures.

Beyond China and the EU, other investors such as the Netherlands, the United States, and Türkiye also play significant roles. Traditionally, the Netherlands has been a leading investor in Kazakhstan, Georgia, Uzbekistan, and Azerbaijan. Last year, Kazakhstan attracted $15.7 billion in gross FDI inflows, though it simultaneously saw a net outflow of $2.6 billion due to repatriation of profits in 2024. The largest declines came from the Netherlands (-$2.1 billion), the United States (-$1.9 billion), Switzerland (-$1.7 billion), China (-$900 million), and Monaco (-$800 million). Most of these funds were previously directed to oil and gas projects, including the Tengiz and Kashagan projects. The completion of expansion work at the Tengiz field and the end of the active phase of investment in Kashagan were the main reasons for the decline in foreign capital.

Instead, the interest in non-resource sectors has been growing, as industrial and manufacturing projects are entering the country. In the first half of 2025, Kazakhstan’s non-oil economy grew by an impressive 6.3%, the fastest pace in 14 years. International firms such as Wabtec, Alstom, Honeywell, PepsiCo, John Deere, and KIA are now investing in Kazakhstan’s industrial and manufacturing sectors, signaling a broader diversification of FDI sources and destinations.

Redistribution appears to be to blame, as the country’s investment sectors are changing. Now, the Middle Corridor is not just a passage linking Europe and Asia, but a vital component driving economic development of the countries along the route. For investors, the focus is shifting to identify how best to seize the opportunities this transition creates. Sustaining this momentum will require governments to provide a stable and predictable regulatory environment in order to attract further investment.

Understanding infrastructure investments

Investments into infrastructure connectivity of Central Asia and South Caucasus can be grouped into several categories. The first is transport infrastructure, where modernization of railways, ports, and ferry fleets has been the most visible achievement. Kazakhstan has upgraded sections of its east–west railway lines, Azerbaijan has expanded the port of Baku in Alat, and Georgia has undertaken improvements to its railways and Black Sea terminals. The Caspian Sea, the corridor’s geographic bottleneck, has seen significant investment in ferry services and port facilities, though operational challenges remain.

The second category is trade facilitation, including customs modernization, single-window platforms, and the introduction of electronic transit documentation such as eTIR and eCMR. These reforms aim to reduce border delays, cut corruption risks, and improve transparency. A third set of investments centers on energy, particularly renewable projects and grid modernization designed to power logistics hubs and industrial zones along the corridor. Finally, digital connectivity is emerging as a critical frontier, with fiber-optic backbones, data-sharing platforms, and pilot cargo-tracking systems supported by both IFIs and bilateral donors.

Overall, transport performance has improved. Transit time from China to Europe via the Middle Corridor now averages 14–18 days, compared to over 30 days by sea and 19 days via the Northern Corridor through Russia. Border crossing time efficiency is also improving with average wait time at Azerbaijan’s road checkpoints falling from 5.8 hours in 2021 to 4.3 hours in 2023, while in Kazakhstan delays dropped more sharply, from 8.2 hours to 4.2 hours over the same period.

Even so, transport costs remain high. Shipping a typical container via the Middle Corridor still costs between $3,500 to $4,500, compared to $2,800 to $3,200 via Russia’s Northern Corridor. While there are significant improvements in terms of reduced time and delays, efficiency remains limited by the higher cost structure.

Nonetheless, freight volumes have surged. Cargo flows through the Middle Corridor rose 2.5 times to 1.5 million tons in 2022, with continued double-digit growth in 2023 and 2024. In 2024 alone, cargo volumes increased by 62 percent, reaching 4.5 million tons, while container traffic tripled in the first ten months of the year. On the financing side, the IFC reported mobilizing $1.568 billion in capital in FY2023 for Central Asia, including nearly $1 billion from private sources, demonstrating the corridor’s ability to attract blended finance.

These trends underscore the rising interest of international private investors in the Caspian region. Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the region’s importance has grown, and its evolving business climate continues to attract global attention. While investors stand to benefit, environmental degradation remains a serious concern, highlighted by both foreign and local stakeholders in their investment assessments.

Capacity development, however, could be best advanced through concrete investments in Middle Corridor segments, such as port rehabilitation, roads, or soft connectivity measures. These projects also encourage governments to adopt environmental and social standards tied to IFI lending requirements. Such spillover benefits can play a significant role in improving development objectives but also assist in combating environmental decline. Long-term Middle corridor improvements are advancing on multiple fronts and, so far, seem to be contributing to the most critical needs for Middle Corridor development. Follow-on investments will hinge on continued donor enthusiasm, efficiency assessments, and demonstrated impact.